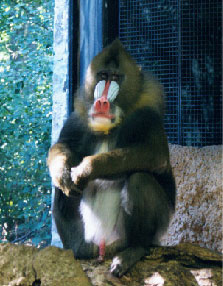

The average body mass for an adult male mandrill is between 21 and 28 kilograms, and for the female it is between 11 and 12 kilograms (Hill, 1970). The mandrill has a dental formula of 2:1:2:3 on both the upper and lower jaws (Ankel-Simons, 2000). The incisors of this species are broad and high-crowned (Caldecott et al., 1996). This species has pronounced maxillary ridges. The mandrill has a relatively short tail. The pelage color ranges from dark brown to charcoal-gray. The penis of the male is colored red and the scrotum has a lilac color. The face also has bright coloration like the genitalia and this develops in only the dominant male of a multi-male group (Dixson et al., 1993; Wickings and Dixson, 1992). Females and juveniles have a duller blue snout and a buffy colored beard (Rowe, 1996). The dominant male also tends to have a relatively heavier rump, larger testes, and higher plasma testosterone levels (Dixson et al., 1993; Wickings and Dixson, 1992).

RANGE:

The mandrill is found in the countries of Cameroon, Congo, Equatorial Guinea, and Gabon. This species is found in dense primary rainforest and sometimes secondary rainforest, gallery forest and coastal forest (Harrison, 1988; Rowe, 1996). Mandrills also can be found on plantations, examples being cassava, Manihot utilissima, and banana, Musa paradisiaca (Sabater Pi, 1972). Mandrills were found to be found in plantations during the dry season (Sabater Pi, 1972).